Recalling the Grim Reality of Workers’ Mobility on May Day

Just a month before International Labour Day (May 1), a group of over 50 young men were camping in the hostel of an abandoned private college building in a small city in northwestern India for two months. They were there to get Russian language training.

Working with recruiting agents, these individuals were selected to participate in a two-month language training programme prior to being offered contracts to work in the bauxite mines located in Severouralsk in Russia's Sverdlovsk oblast, a region renowned for its extensive underground bauxite mining.

The participants were primarily from small and marginal farming families across various regions of India had varied work histories: they had worked as casual workers, construction workers, contract employees in government and private offices, taught in private schools and a few of them were fresh college graduates from small town colleges.

But they had one thing in common: none of them were experienced miners and most had never seen a mine, let alone an underground one.

Nevertheless, they were committed to travel to Russia. Their agents informed them that their work visas would be obtained by the mining company with a two-year employment contract on salaries ranging between $1,000 and $3,000 a month based on their performance, with boarding and lodging provided.

They were not clear if meals were included in the package. Their understanding of Russia’s geography and the war’s status was limited, but they knew the value of the ruble and the rupee remained equivalent.

The candidates calculated the potential earnings in their heads, multiplying the US dollar salary figures with 86, compared it to their current wages of Rs 12,000 to 17,000, and felt optimistic.

The agents assured them that their phones would function, though concerns arose when the topic of blocked WhatsApp calling and restricted YouTube access in Russia surfaced, inciting anxiety about maintaining communication. WhatsApp calling, after all, was vital for staying in touch with families.

However, when a confident young man in the group suggested that VPN services could circumvent these restrictions, it provided the much-needed assurance they were seeking amidst numerous uncertainties still occupying their minds about food availability, severe cold weather, operating heavy drilling machines in underground mines and permissions to visit home.

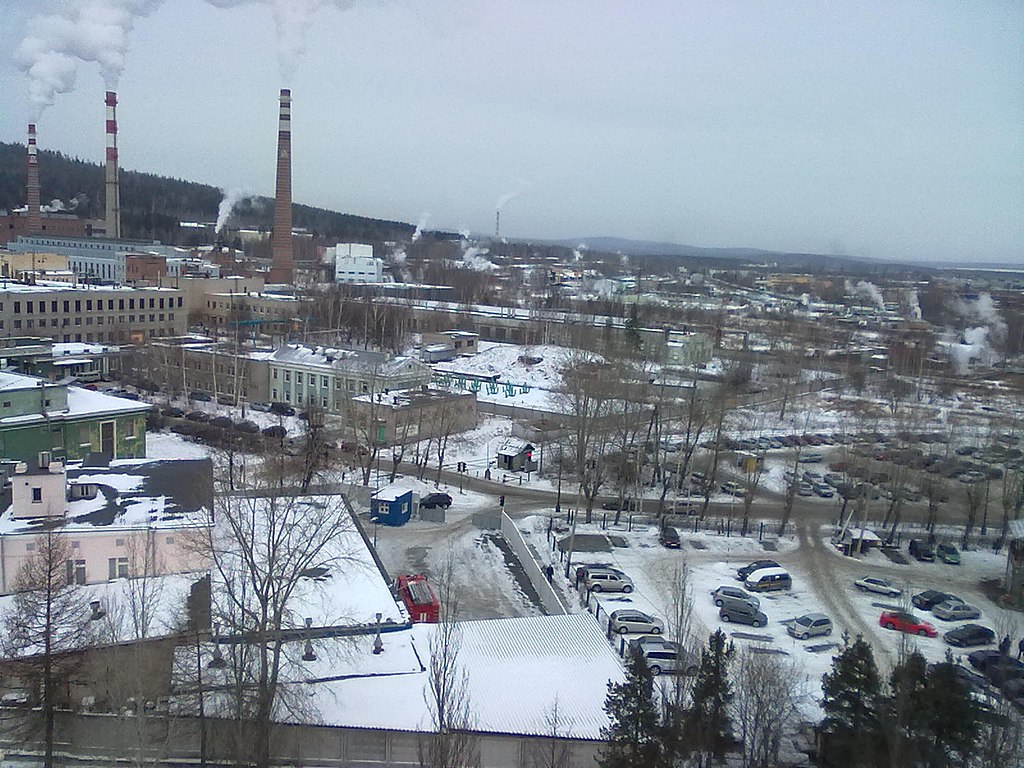

Upon returning after meeting with these prospective mine workers, we wondered if they really knew what they were getting into. File photo of Novouralsk in Sverdlovsk oblast. Photo: Денис Александров/Wikimedia Commons/CC BY-SA 3.0.

Upon returning after meeting with these prospective mine workers, we wondered if they really knew what they were getting into. We were reminded of Hemil Ashvinbhai Mangukiya, a 23-year-old from Surat, Gujarat who died in a Ukrainian airstrike last year in Donetsk near the Russia-Ukraine border.

Hemil had left Surat to work as a security helper for the Russian armed forces. He ended up performing tasks like digging trenches, loading guns and lobbing grenades. Refusing to fight meant digging more trenches and sleeping without food in cold trenches.

Reports had emerged in March last year of an Indian youth from Kerala who was recruited to northern Israel to work in a large farm and who was killed by a missile fired by Hezbollah from Lebanon.

He was recruited amidst news of the Indian and Israeli governments' agreement facilitating the recruitment of 42,000 Indians to work in Israel’s construction and nursing sectors, which was later expanded to include agricultural work.

The youth from Kerala, however, was a part of about 800 Indians – most of them from southern Indian states – who had moved to Israel by the end of 2023 to work in agriculture.

This movement of labour was however, not part of the two governments’ agreement. “These people left for Israel privately. They were mobilised by local agents, whom they had to pay about Rs 400,000,” a local politician was quoted as saying following the killing.

The young worker’s parents told the media that during phone calls with their son, they would hear the sound of missiles and mortars in the background and that they asked him to move to a safer area two weeks earlier. However, he couldn’t move out as he did not get consent from his sponsor, the father was quoted as saying.

A few months earlier, the government of Uttar Pradesh had advertised 10,000 jobs for skilled construction workers to work with Israeli building firms. This was in response to a formal a government-to-government agreement signed in late 2023 to facilitate the recruitment and deployment of workers. The skill tests for Indian workers heading to Israel were organised by state governments in collaboration with the National Skill Development Corporation (NSDC).

In Uttar Pradesh, the ITI Lucknow was a designated centre for conducting these tests. The test was preceded by a complicated process of registration. Only candidates with an application form with the sign and seal of the ITI and registered with the labour department were allowed to participate in the mandatory skill test, where the aspirants' ability to do shuttering work, tile and marble fitting, and wall plastering among other tasks were tested.

As the newspapers reported at that time, thousands of candidates gathered to get registration forms and queued up for the skill test to try their luck against 10,000 vacancies for construction workers in Israel. The Israeli job offer was a salary of Rs 1,37,250 per month besides a fund bonus of Rs 15,000.

File: A recruitment drive for jobs in Israel at ITI Lucknow. Photo: Asad Rizvi.

The same advertisement appeared in Haryana and the Haryana Kaushal Rozgar Nigam and the NSDC collaborated to conduct similar skill tests. Thousands gathered in the grounds of a university in Rohtak in the cold foggy days of January 2024.

The news of workers dying in crossfire in the war-torn country didn’t deter the workers. Everybody wanted to go, as the interviews with prospective candidates that circulated widely on social media revealed. The selected candidates received pre-departure orientation training to prepare them for life and work in Israel.

A story related to these two recruitments which did not make the headlines but surfaced shortly after the workers left revealed that on their arrival in Israel, when they were assessed for their ability to perform the jobs they claimed their skills for, many Indian workers were found to be unfit.

Having spoken to Israeli and Indian officials, construction executives and workers, the Indian Express reported that the problem was an assessment process that “over-promised and under-delivered when it came to workers' abilities”. As a result, a large number of workers were reportedly demoted to the unskilled category.

The external affairs ministry however maintained that the reports were not correct and in an official response to the news item claimed, “as per information that has been provided to us by the Israeli side, most of the Israeli companies are satisfied with the working of Indian workers”.

Labour unions in India protested and opposed the government’s agreement. “India’s stated policy is to bring back people from war-torn and conflict areas…,” they asserted.

Ten of India’s biggest trade unions issued a strongly worded statement, urging the government to not send Indian workers to Israel amid the ongoing war on Gaza.

“Nothing could be more immoral and disastrous for India than the said ‘export’ of workers to Israel. That India is even considering ‘exporting’ workers shows the manner in which it has dehumanised and commodified Indian workers,” the statement said.

The Construction Workers Federation of India, another major union, also opposed “any attempt to send the poor construction workers of our country to Israel to overcome its shortage of workers and in any way support its genocidal attacks on Palestine”.

In response, external affairs ministry spokesman Randhir Jaiswal stated, “… Labour laws in Israel are very strict, robust. It's an OECD country, therefore labour laws are such that it provides for the protection of migrant rights, labour rights. On our part, of course, we are very conscious of our responsibility to provide security and safety to our people who are abroad.”

What’s going on?

Indian workers today are willing to accept the world’s most dangerous jobs and to traverse the most dangerous dunki routes. Their choices stem from their desperate need for jobs, better living conditions and higher wages. This is a testimony to their acute financial distress.

Labour-scarce advanced capitalist countries offer wages which are much higher than in India. Once the labour makes it to these countries, jobs are available as they are insourced to work in crucial sectors such as construction, transport, agriculture, mining, health and domestic and care work that the resident labour avoid.

Throughout the history of capitalism, the migration of workers has been a key driver of capital accumulation, with individuals moving across borders to seek better opportunities and improve their living conditions, often spurred by poverty.

The mobility of labour is perhaps the most significant form of engagement between the advanced capitalist countries and the rest of the world. This movement of workers takes different forms – sometimes on permits as guest workers and student visas and often as undocumented workers to work at a fraction of the wage of resident workers.

They work in harsh conditions and their meagre savings obtained by working long hours and living in poor conditions are sent to families back home, the sphere of the reproduction of labour power. These savings are sometimes given fancy names such as a ‘remittance economy’.

The fund-banks advising the developing south on development strategies emphasise the importance of remittances as a contributor to economic growth and leveraging remittances for development purposes.

Today, the reports of labourers deported from the US are gradually fading from our collective memory. Representative image from X/@PressSec.

It is perhaps true that remittances help to assuage poverty among these families, but there is no clear evidence of their contributing to growth or infrastructure development in the sending countries. Still, the sending states advocate for a less restrictive movement of labour with the goal of pushing the unemployed youth out.

This was evident during the G20 in India, where labour migration topped L20 discussions. The Modi government tried hard to sell Indian labour to the visiting leaders from the global North.

In the receiving country's labour market, these workers are perceived as competitors and responsible for driving the domestic wage lower. While the progressive labour movement talks about ensuring decent jobs with workers’ rights for migrants and residents alike, the popular majority wants to see restrictions on immigration. The populist political parties play on this sentiment.

Interestingly, the immigration policy restricting labour migration is unswervingly countered by capital, which needs cheap labour. Recently, when Canada threatened to send thousands of migrant workers back, the employer lobby swung into action, working hard to argue for more immigrants. The media reported pushback from business groups who said there weren’t enough domestic workers available to sustain parts of the economy.

Labour migration is thus not the simple geographical mobility of workers, it is about the transfer of labour power for accumulation in advanced capitalist countries, a process in which developing states are deeply implicated.

The post-1980s world economic order created hope for working people in developing economies that there will be (good) jobs in the manufacturing and service sectors for the vast majority of workers domestically and also opportunities to earn a better living by finding jobs in the rest of the world through unrestricted mobility.

But the spread of investments and manufacturing followed where labour was the cheapest and the new economic order produced supply chains that were based on the race to the bottom.

Can global protocols be negotiated to ensure non-precarious mobility, decent wages, safe working conditions with equal rights and opportunities to prevent workers from being used to undercut each other, and to fight against discrimination, racism and labour market segmentation?

No easy answers there. The dissatisfaction with the labour market outcomes that accompanied globalisation has failed to produce any alternative discourse for an international economic order that prioritises the interests of labour. The recent Trump proposals and the trade-related initiatives to help the US fulfil its larger dream for re-industrialisation are only going to intensify the misery for labour worldwide.

What next?

In the last decade-and-a-half, the real incomes of workers have more or less remained stagnant while corporate profitability has soared to a 15-year high. Despite the hype created by the Modi government around Make in India, Skill India, Startup India, Digital India and the promise of creating two crore jobs in the non-agriculture sector annually, agriculture remains the option for older and less-skilled workers.

The declining share of manufacturing in employment has pushed the youth towards non-manufacturing and service sectors, reflecting insufficient growth in formal employment. This mismatch between labour supply and demand has led to increasing unemployment among the youth, particularly at higher levels of education, which indicates a disconnect between educational attainment and employment.

Over 60% of young regular workers are ineligible for social security, pointing to the entrenched nature of informality in India’s labour market. Both formal and informal sector workers face limited wage growth, but the latter, who constitute the majority of India’s labour force, experience far worse conditions marked by low pay, job insecurity and a lack of social protection.

Indian workers often lack the skills demanded by higher-value industries, making them less competitive and effectively unemployable in sectors that drive global growth.

Subcontracting in formal industries, especially more labour-intensive tasks, to the informal sector, extracts significant value while leaving informal workers with minimal returns. This arrangement underscores the systemic inequities in India’s labour market, where the benefits of economic growth are concentrated among owners of capital and higher-level employees, while the vast majority of workers operate in a labour market that prioritises capital gains over labour needs.

Also read | 'Not Slaves, But Coolies': Must Confront Questions 'Government-Sponsored' Labour Export Raises

Today the reports of labourers deported from the US are gradually fading from our collective memory. The images of handcuffs and chains are no longer prominent. The humiliating crackdown on “illegal immigration” and its impact on the lives of thousands of vulnerable Indian citizens who had risked everything to make their way to America no longer haunt us.

The arduous journeys they took to clandestinely cross the US border, which would have cost their impoverished farming families lakhs of rupees in fees to the agents, have also receded from our collective consciousness.

The distressing details of the US detention centres where individuals were held after being apprehended for attempting to cross the border – the cold air conditioning units kept constantly on, turbans discarded in trash bins, water and food withheld – and the fear that enveloped them and the uncertainty regarding their futures are gradually disappearing from public discourse.

The prime minister not willing to do much to help undocumented Indians in the US amid Trump’s crackdown should not surprise anyone. He meekly responded that his government was “fully prepared to bring back illegal migrants … vulnerable and poor people of India who are fooled into immigration … the children of very ordinary families lured by big dreams and big promises … through a human-trafficking system.”

He shared not even a vague plan about smashing the networks of the “human- trafficking system” who are hoodwinking the children of very ordinary families.

As the children of impoverished peasantry landed in Amritsar on board US defence planes, chained and handcuffed, if anyone protested it was the farmers’ unions, who took to the streets of Punjab demanding that the government take responsibility for the debts incurred by the families of the returning youth.

They asked the government to break the human trafficking networks and, above all, demanded that the government rethink its development policy, which prioritises capital’s needs over their own and pushes their children to international migration circuits for exploitation. They asked the government to create jobs for the sons and daughters of crisis-ridden rural peasantry so that they don’t have to take dunki routes to enter unwelcoming places.

It is the farm labour and farmers’ unions who protested when the US trade delegation came to India in late March, demanding that India keep the interests of labour and farmers at the centre of trade negotiations.

These movements saw that the misery associated with labour migration is part of the order of global capital accumulation and that workers’ rights, safety and just compensation are linked with the fight against this order at home and offering resistance to the diktat of global capital everywhere.

It is this resistance and increased solidarity within and among justice movements that is the only way to change the current policy orientation and make it labour-centred, where the due rights and privileges of workers are protected.

Atul Sood is a JNU professor. Navsharan Singh is an author and activist.

This article went live on May first, two thousand twenty five, at twenty-eight minutes past eleven at night.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.