The Redevelopment of Dharavi will Destroy the Livelihoods of Those Who Work in Small Businesses

Dharavi, known as Asia's largest slum, is very unique. It has migrants from states like Bihar Uttar Pradesh, Bengal, Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh and Gujarat making it multi-ethnic. Its uniqueness is also because of its sustained and vibrant economic activities – manufacturing and commercial. Unemployment is said to be low, though at the same time, the majority of employment is in the informal economy largely within Dharavi.

There is a diversity of occupations carried out in Dharavi, from garments and apparel, leather goods manufacturing, and waste recycling to pottery and snack making. In addition to this, there are big godowns of raw materials needed for various occupations to finished products of day-to-day use like mats, leather, pottery, snacks and unstitched cloth. It also comprises substantial residential, both ownership and rental, units in Dharavi.

The latest Dharavi Redevelopment Plan (DRP) is being carried out by Adani under its real estate arm Adani Realities. The project is led by Navbharat Mega Developers Private Limited (NMDPL), and is a joint venture between Adani and the Maharashtra government. The model of redevelopment shall be like the Slum Redevelopment Scheme of the city's Slum Rehabilitation Authority as per section 33 (10) under the Development Control Regulation.

Past and present efforts at Dharavi redevelopment

Rehabilitation initiatives for all slums, not only Dharavi, have been spurred since independence for many reasons, including humanitarian, employing a variety of methods, such as relocation, and ultimately rehabilitation. Often, as is the case when slum dwellers are ‘evicted’, these measures have been repressive.

One slum area improvement programme was carried out in the early 1970s to provide basic amenities to slum dwellers in Dharavi. The government’s approach towards slum dwellers was to uproot them with the help of the police – massive evictions were carried out that encountered stiff resistance from all quarters, as this report shows.

In 1987, the government’s own Maharashtra Housing and Area Development Authority (MHADA) was designated as the Special Planning Authority and it developed 27 seven-storied buildings under the Prime Minister’s Grant Project. The project even today remains incomplete. The phase of liberalisation saw market driven solutions for welfare. A Slum Rehabilitation Authority was appointed to implement the Slum Rehabilitation Scheme. Since the announcement of the SRA in 1995, 86 schemes have been approved by 2004 in Dharavi. Many could not take off due to the presence of a large number of commercial and industrial units. The schemes were scattered throughout Dharavi, with most development occurring along existing roads.

Post the announcement of SRS, Mukesh Mehta a non-resident Indian and urban planner proposed a plan to develop Dharavi in the late 1990s but even he had to wait for five years to get the government’s nod.

In 2004, the government approved the proposal for the Dharavi Redevelopment Project (DRP). It was to be developed with investment from global corporations. The plan faced stiff resistance as it was not developed with people's participation. The original DRP was a residential-focused redevelopment plan intended to rehouse eligible property owners in 300 square feet of space in seven-storey tower blocks, complete with standard infrastructure like roads, water, and electricity – similar to the model used in SRS projects. The SRA would select five developers to reconstruct five designated sectors of Dharavi. Developers would receive land use incentives like additional Floor Area Ratio (FAR) – four over the existing 2.5 – and/or transfer of development rights (TDRs) to build extra units they could sell in the open market to offset the cost of rehousing residents. Once the DRP was sanctioned every other development was stalled – roads, drainage, toilets, and water connections.

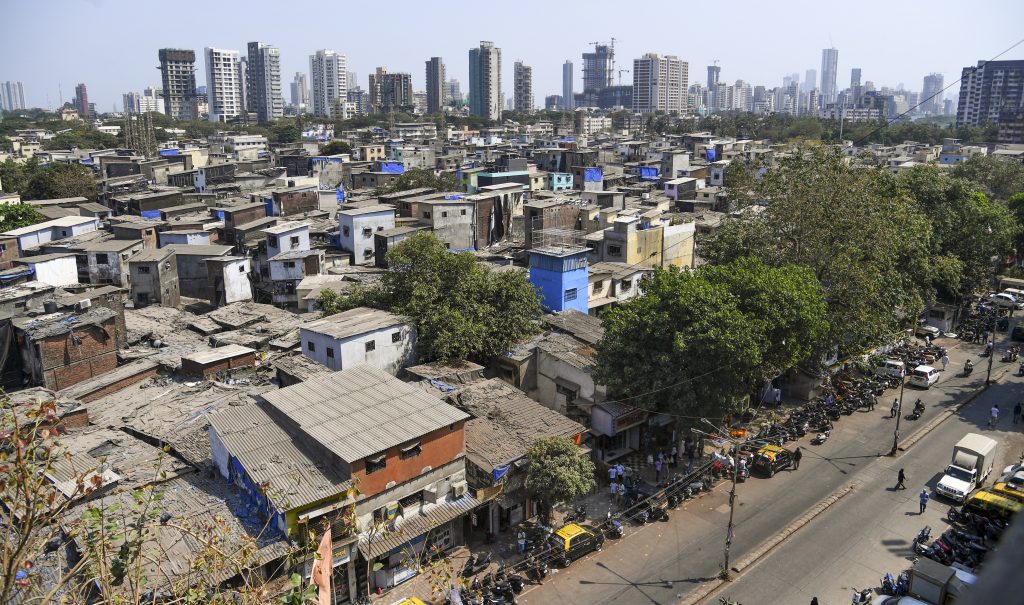

Mumbai: A view of the Dharavi area, in Mumbai, Friday, April 11, 2025. Photo: PTI.

In 2018 one more attempt to develop Dharavi was undertaken, when a UAE-based company, Seclink Technologies Corporation, won the contract for the project. SecLink’s tender was cancelled on the grounds that there was a significant alteration to the original tender due to appendage of 45 acres of railway land.

In December 2022, it was announced that Adani had secured the project. This development sparked widespread criticism, with allegations that the government had shown undue favouritism toward a particular corporate entity. These concerns have raised serious questions about the transparency and fairness of the entire tendering process.

In January 2023, Hindenburg Research reported that the Adani Group had engaged in brazen stock manipulation and accounting fraud over decades. Following these allegations, Dharavi residents do not find the group trustworthy to complete the project.

Also read: Four Issues SEBI Raised (Or It Couldn’t) in the Adani-Hindenburg Matter

But this did not stop the group’s plan in Dharavi. It is moving at a brisk pace. A door-to-door survey is being carried out since last March. Around 69,000 units have been fully documented, and nearly 1 lakh have been numbered. While surveying residential units was relatively straightforward, the real challenge lies ahead: determining eligibility, categorising different housing typologies, and assessing the complex economic fabric of areas like Kumbharwada, Koliwada, and the 13th Compound – the waste recycling hub. These neighbourhoods are marked by diverse occupations, multi-layered worker arrangements, and unique living conditions which makes things complex.

Inside Dharavi: Realities of informal economy workers and the question of rehabilitation

Dharavi is the hub of small-scale manufacturing and industrial units. The commercial and industrial structures mainly operate in garments, plastic recycling, dyeing, aluminium moulding, leather processing, farsan making, pottery and box making as commercial and industrial units. Apart from the se commercial activities recycling, farsan making and pottery are other commercial activities carried out in Dharavi. A general figure usually mentioned is that the commercial activities in the vast slum generate $ 1 billion per year.

Tens of thousands of workers are employed in these units. The current plan is mute on the rehabilitation of workers. Workers in these units are migrants from Bihar, Bengal, Uttar Pradesh, Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu and Gujarat. Most of them migrated to Mumbai to escape acute poverty in their home states. Displacement of their workplace and work shall not just impact them but impact over lakh families who are dependent on these migrants. There is no clear plan for rehabilitation of these workers. The tenement owner shall be compensated in the form of a commercial or industrial unit but the workers shall be forced to dwell in these units as was the arrangement before.

Another important economic activity that takes place in Dharavi is home-based activity such as papad-making, bidi-making, zari work, leather goods, pickle-making and button-making. Many of these economic activities are carried out from their homes and these will be dispersed. Past experience shows that the linkages with the parent manufacturers get destroyed once a unit is moved and home-based work does not revive in the same form.

What is particularly alarming is the government's proposal to rehabilitate ‘non-eligible’ tenements in areas like the Deonar landfill, salt pan lands in Wadala and Kanjurmarg, and the Kurla Dairy plot. Deonar is an active landfill site and completely unfit for human habitation – relocating people there is a blatant violation of human rights. It reflects a systemic failure on the government’s part to provide even the most basic dignity and care to the working-class communities of Dharavi.

A man and his child look out of their window in Dharavi, Mumbai. Photo: PTI

But the question arises, why, after all these years, this urgency to develop Dharavi suddenly?

Next door to the biggest slum is one of the most expensive pieces of Mumbai real estate – the Bandra Kurla Complex, which was carved out of marshy lands and now is home to some of the biggest names of the Indian and international corporate sector. Many ancillary projects have been announced to improve infrastructure and transportation to and from BKC. BKC has taken the place of south Mumbai, which at one time was the corporate hub and the most prestigious address in the city. No longer. The buildings are looking old and cannot offer what BKC can – modern structures with parking, fancy restaurants and larger office spaces.

But there is a problem. Land in the BKC, which also houses residential buildings, is running out. More is needed.

Enter Dharavi with its estimated 600 acres. The additional land will come from redevelopment of this slum and also of the smaller slums around the area. The current residents, who have lived there for generations, while be given modest properties of their own or shifted out to distant places, and in the land that will be freed, smart new offices and luxury towers will come up.

Yet, while the current Dharavi Redevelopment seems to address the needs of the people of Dharavi, it will eventually and the city at large. Dharavi is a complex ecosystem of residences, rentals, commercial and industrial units. On paper, the proposed plan addresses each of these but in reality, it will destroy the lives and livelihoods of toilers who find employment in these commercial and industrial units. It will disrupt occupations like garment manufacturing and allied industries, leather bags and accessories, waste recycling, fishing and others. It will also displace home-based work that is carried out to support these occupations. It will also increase the drudgery of people in the construction industry and domestic work. Work will be lost for men and women in large numbers. It will not impact the migrant workers and their families here but their families back in their native states – Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Bengal, Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu and Gujarat. The need at the present juncture is to support the already existing economies when every 3rd person in the working age is unemployed.

The proliferation and expansion of the service industry (a project of capital) in this case the coming of Bandra Kurla Complex and its need for further expansion shall be mindlessly replicated. The fear is that the development discourse will be dominated by the creation of new business districts and the need for supplementary land will disrupt the lives of the toilers. And most of all, moving people on live landfills and salt pans amounts to a violation of human rights.

Shweta (Tambe) Damle is the founder and Director of Habitat & Livelihood Welfare Association and on the Executive Committee of the Working Peoples’ Coalition. She is based in Mumbai. She can be reached at shweta.tambe@gmail.com.

This article went live on May twentieth, two thousand twenty five, at sixteen minutes past eleven in the morning.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.