Keki Daruwalla, the Sensitive Intelligence Officer Who Wrote Poetry

Keki Daruwalla was ill on July 9 when our Sahitya Akademi held an online event to honour him by arranging a discussion of its publication ‘A House of Words - Festschrift: In honour of Keki N. Daruwalla’ edited by Usha Akella. The event was attended by some of India’s well-known poets and writers like Basudhara Roy, Harish Trivedi, Malashri Lal, Namita Gokhale, Ranjit Hoskote and Sukrita Paul Kumar. Festschrift in German means “celebration writing”.

The moderator was Sanjukta Dasgupta. All of them, including Usha Akella, spoke warmly about Keki, his poetry, his compassion, his aphorisms, or ‘Kekisms” as they called and how he was always empathetic towards younger poets. One more such event was held later by the Sahitya Akademi.

Keki and I belonged to the Indian Police Service but went on deputation to our foreign intelligence (the Research and Analysis Wing or R&AW) later in our career. Both of us were born in 1937 in two neighbouring countries that were once part of India: I in Yangon and he in Lahore. However, we met each other only in 1976 when I joined R&AW from Maharashtra state after doing grassroots policing for 17 years.

He had joined our foreign intelligence earlier after working as assistant superintendent of police in Uttar Pradesh from 1959, and after a spell with the erstwhile Special Service Bureau till 1965. Also, he had the honour of being selected as the special assistant to the then-Prime Minister, the late Charan Singh, between 1979 and 1980. After this he spent a year at Oxford University on study leave as a “Queen Elizabeth II House Fellow” during 1980-81.

From the early 1980s we worked together in the cabinet secretariat continuously until 1995, when we retired.

Keki’s last post was as chairman of the joint intelligence committee (JIC), which had the ultimate responsibility of integrating and interpreting strategic intelligence for the cabinet. This is because agencies often produce conflicting intelligence on security-related subjects, needing an able arbiter to sort out the differences.

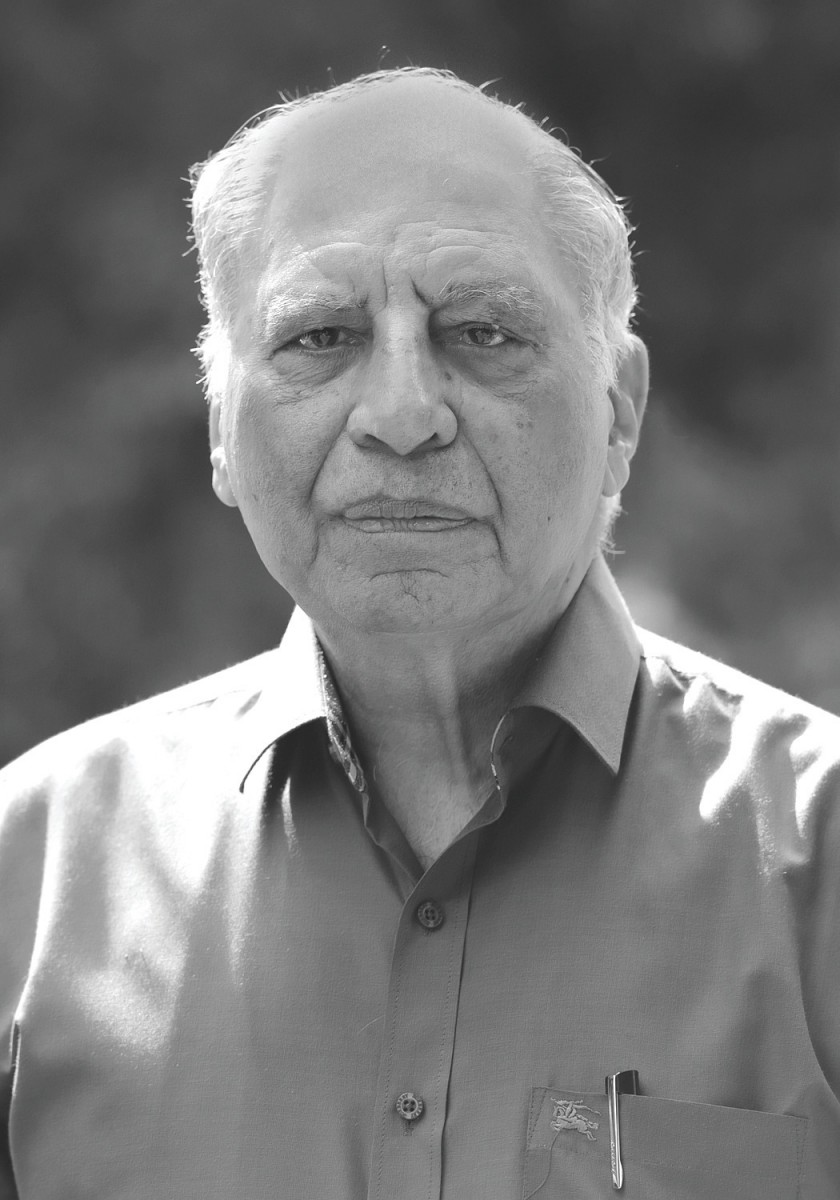

Keki Daruwala. Photo: Speaking Tiger

Very often the essence of an emerging trend is lost in the flood of information. On the other hand, agencies produce incomplete intelligence in several cases and toss it to the government for further action. That is why decision makers often complain of not receiving “actionable information”.

In such circumstances, the office of chairman JIC assumes a very important role, although less visible, where the chief’s analytical and interpretation abilities as the highest intelligence arbitrator are put to test in presenting a holistic picture to the cabinet.

When Keki was chairman JIC, there was a dispute between R&AW and our army on the assessment on the number of Chinese divisions in Tibet, and it was left to Keki’s persuasive skill to iron out our differences to present a composite picture to the cabinet. In other words, the JIC was and is a super-intelligence evaluation body needing much more skill than mere intelligence collection.

Post retirement, Keki was appointed as member of the National Commission for Minorities from 2011 to 2014, when he had to undertake visits to different parts of the country to investigate cases of injustice against minorities. This was also a heavy responsibility as several cases of violation of human rights were reported during that period, needing personal visits by members of the Minorities Commission.

In 2014, 19 years after his retirement from government service, he was awarded the Padma Shri by the president.

In such circumstances it was amazing how Keki could also lead a ‘double life’ as an internationally recognised writer-poet, who produced 17 books of poetry, short stories and novels. His books have been translated into Spanish, Swedish, Magyar (Hungarian), German and Russian. He also used to attend poets’ conferences all over the world. In 2017 he was honoured with the “Poet Laureate Award” by the Tata LitFest, Mumbai.

His compassion for the common man was discernible even early in his career as a police officer in 1971, when he wrote a poem ‘Routine’ describing the scene of police firing: “Depressed and weary we march back to the lines”.

Years later the same empathy was seen in ‘Swamy and Friends’ (July 2021), describing the tragic death of Father Stan Swamy in prison: “If you had no mai-bap, you were left to fate; no bail, more jail”.

It was a great achievement for a police man like Keki to become such a renowned poet even at a young age and to win the Sahitya Akademi Award for his collection of poems The Keeper of The Dead in 1984. Another book of poems, Landscapes, won him the Commonwealth Poetry Award (Asia) in 1987. His first novel For Pepper and Christ (2009) was shortlisted for the Commonwealth Fiction prize in 2010.

How did he do it? One of his common ways to ‘recharge’ his creative mind was by holding small marbles in his palm and gently shaking them! I found that in between his heavy official work, he would take time off, go into isolation in his own house and produce those gems of books.

Of all his works, my favourite is For Pepper and Christ, which gives a fictional account of Vasco da Gama’s voyage to my home state Kerala. I was amazed how he could describe the 15th-16th century Calicut (Kozhikode) with such precision, not having visited that city even once. He told me that he used to do research for the book at the American University library in Cairo while visiting his younger daughter Rookzain.

My other favourite is his ‘Map-Maker’ poem (2002): “Perhaps I’ll wake up on some alien shore in the shimmer of an aluminium dawn, to find the sea talking to itself and rummaging among the lines I’ve drawn; looking for something, a voyager perhaps, gnarled as a thorn tree in whose loving hands, those map lines of mine, somnambulant, will wake and pulse and turn to shoreline, sand”.

It is said that sometimes creative writers turn out to be good intelligence officers as both need curiosity, observation, imagination and constant questioning to find answers. That was true of Keki.

Vappala Balachandran, a former special secretary in the cabinet secretariat, is the author of four books. Views personal.

This article went live on September twenty-seventh, two thousand twenty four, at three minutes past nine at night.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.