In the Heart of Delhi, an Attempt to Render Visible the People of Bangladesh's Hills

On a spring evening in March, a culturally vibrant and important art space in south Delhi, Khoj, opened its venue to the exhibition ‘No Steady State’. The exhibition was in fact, five smaller exhibitions curated by the fellows of the Curatorial Intensive South Asia (CISA) 2024, a program run by the organisation along with the Goethe-Institut/Max Mueller Bhavan, New Delhi.

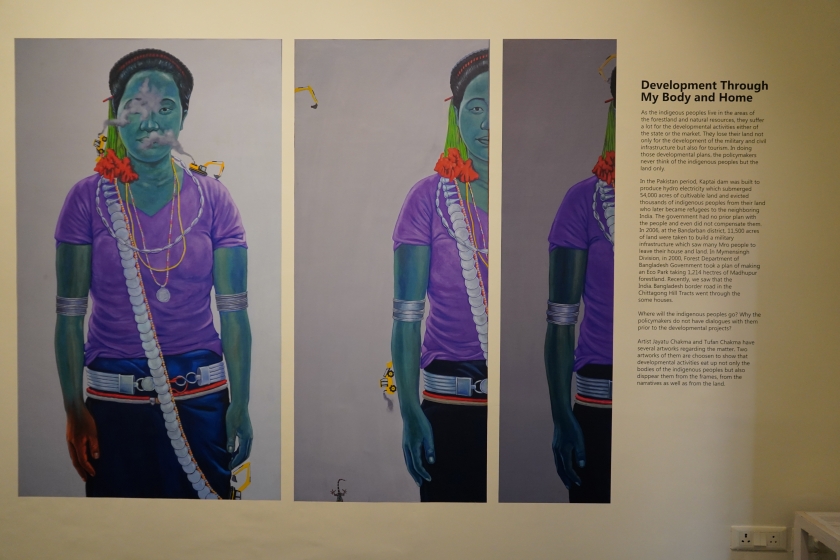

As one entered Studio #1 in the courtyard of Khoj, a life-size triptych of a woman greeted the eyes. It was no ordinary woman. Painted in hues of purple, blue and green, the images unsettled the viewer. The subject appeared to be an ‘ethnic’ woman.

Jayatu Chakma’s artwork, ‘Extinguished Entity’, depicts a reality that not many in the heart of Delhi are aware of, a reality that is unfolding in the Chittagong Hill Tracts (CHT) of Bangladesh and other frontier regions of South Asia, including India.

The triptych shows a Chakma woman being slowly erased of her identity and very presence from the landscape and memory of the region. With smoke billowing out of her body in wisps and heavy earth movers crawling across her, her body and presence are slowly erased away in this artwork.

But this is no hyperbole. This is the cost of “development” that many Indigenous peoples in the region and also in other frontier areas like the northeast of India are paying.

The purplish colours of her complexion add to the eeriness of the whole spectacle, where her identity is also dehumanised. At the altar of ‘development’, the Indigenous peoples are transformed into the non-human, the invisible.

This artwork along with others was part of the curatorial project of a young Chakma filmmaker and curator, Adit Dewan, also a fellow of the CISA 2024. Titled ‘Alienation: The Case of the Indigeneity and the Indigenous Peoples of Bangladesh’, Dewan’s exhibition spoke about political, social and cultural identity crises of the Indigenous peoples of the CHT through the powerful and poignant artworks of Indigenous artists of the CHT like Joydeb Roaza, Tufan Chakma, Jayatu Chakma and others.

At the altar of ‘development’, the Indigenous peoples are transformed into the non-human, the invisible. From ‘Alienation’ by Adit Dewan, presented as part of ‘No Steady State,’ a group exhibition under Khoj and Goethe CISA 2024, held at Khoj Studios in March 2025. Photo: Shaheen Ahmed.

Why this exhibition matters

Almost a decade ago, noted Bangladeshi photographer and activist Shahidul Alam held an exhibition in the art district of New Delhi in Lado Sarai on the life of Kalpana Chakma.

Titled ‘Kalpana’s Warriors’, the exhibition served as a memorial to the fiery young Indigenous activist, who was abducted reportedly by personnel of the Bangladeshi military in 1996 and has never been found.

Nearly 20 years after her illegal abduction, Chakma was presumed dead and Alam’s exhibition paid obeisance to her and her fellow Indigenous activists who persisted with their efforts to locate and release her.

Writer Kaamil Ahmed describes her as someone “… who did not fit into the country’s national image – Bengali and Muslim – even in a state built on the back of a movement for language rights”.

Alam displayed a series of laser-etched photo portraits in the exhibition along with other paraphernalia connected to Kalpana Chakma. These portraits were etched on straw mats, which are an integral part of the everyday lives of the Indigenous peoples or the Jumma people of the CHT.

That exhibition, striking as it was tragic, was my first encounter with the region called the CHT and the lives and issues of the Indigenous peoples who call that region their home. We shall understand through the current exhibition that the political and cultural issues which Kalpana Chakma struggled for are still relevant today.

But what is the geographical and cultural landscape of this region that we know as the CHT?

Academic and scholar of the CHT, Shapan Adnan in his book Migration. Land Alienation and Ethnic Conflict: Causes of Poverty in the Chittagong Hill Tracts of Bangladesh, writes that the “CHT lies in the southeastern part of Bangladesh, adjoining the international boundaries with India (the states of Tripura and Mizoram) and Burma (Myanmar)”.

He continues, “The CHT has a number of features which distinguish it from the rest of Bangladesh. Its hilly and forested terrain is suitable for jum or swidden cultivation. The pursuit of jum combined with hunting and gathering in the forests, gives the economy, society and material culture of the CHT many distinctive characteristics compared to the rest of Bangladesh”.

It is from the word jum that the term Jumma has been derived to describe the Indigenous peoples of the CHT, as jum cultivation has traditionally been the “cornerstone of the way of life of all the different Indigenous groups”.

The history of the CHT has been one of enduring colonialism from the time of the British in the Indian subcontinent and neo-colonialism up to contemporary times. Dewan’s curatorial intervention served as a decolonial testament in the heart of Delhi and rendered visible the invisible and their resistance against the mighty state apparatus.

Dewan's curatorial intervention

Dewan states in his curatorial note that the Indigenous peoples of Bangladesh are facing an identity crisis due to a loss of subjecthood. This loss has been due to the non-recognition of the Indigenous peoples by the Bangladeshi state, which in turn has led to the Indigenous peoples to become alienated from their very existence.

“Bangladesh does not recognise the Indigenous peoples and rather states that constitutionally Bangladesh shall be known as Bangalees as a nation. Bangalee is the largest and dominant linguistic and cultural group which comprises 98% of the total [Bangladeshi] population,” Dewan writes.

He further states that there are restrictions on the usage of even the word “Indigenous”, and Bangladesh defines the peoples of the CHT as either ‘tribals’, ‘a minor race’ or as an ‘ethnic sect’.

Dewan himself delicately explores his alienation from his own Indigenous identity due to state oppression in his short video artwork, ‘What is my next identity’, which is a single-channel four-minute video consisting of still photographs, videos, news footage and also documentary footage.

The artwork starts with an expansive view of a lush green meadow over which the narrator, Dewan, says, “This is our village.” The next shot is of dense foliage in what looks like a jungle, of which the narrator explains, “This was our open latrine.”

In this mediation of nostalgia on the artist’s experience growing up as an Indigenous child in Bangladesh, he uses the landscape and natural space of the CHT to evoke contrasting memories. For instance, in one shot of the village he remembers he saw Bangladesh army personnel in that space, and in another space in the same village he remembers seeing members of the Shanti Bahini guerilla group.

Dewan uses the intimate domestic space of his home in his unnamed village to delve into the mytho-cultural and political history of the Chakma community. He starts by exploring how he was born as a Chakma, but the identity that the Bangladeshi state has imposed on him is that of being an upajati, which he describes as a Bengali word meaning ‘sub-nation’ or ‘sub-group’.

Anthropologist Ellen Bal argues that the term upajati “… refers to uncivilised, less developed and innocent peoples who live more or less isolated from the ‘mainstream’ of ‘civilised’ Bengali society”.

This state-sanctioned term clearly implies that upajati “is a derogatory concept which suggests that they are of a lower order than the Bengalis, who form a jati or nation, whereas an upajati is a mere sub-nation,” Bal further writes.

While navigating the complexities of his own identity, Dewan realised that he is an Indigenous person of the CHT when he went to university, but as he has described, the state does not recognise the Indigenous identity of the communities of the CHT.

A poignant shot plays of Dewan standing in the middle of a stream in the midst of a valley where he mediates over his identity when he says, “living in the puzzle [of] your own identity is self-alienating. I am not the one who decides who I am”. This mediation in a nutshell navigates the struggles of the Indigenous peoples of this region.

Towards the end of the video, Dewan shows a still photograph of him in casual Western wear with black shades on his face posing outside a tin shed, of which he remarks, “we have a tin-shed low commode in place of an open latrine”.

Dewan’s art and his curatorial experiment must be understood through the decolonial turn in postcolonial scholarship and understanding of the arts. The exploration of the struggles of being an Indigenous artist points us to a decolonial aesthetics of understanding resistance art.

Philosopher Don Thomas Deere argues about decolonial aesthetics as pointing to a “critique” of the “coloniality of space”. Which means that decolonial aesthetics opens us up “to non-objectifying modes of seeing, feeling and encountering space” when encountering art by Indigenous artists. This is the experience we have when we see Dewan’s work as a decolonial testament of a young Chakma artist.

When Dewan talks about the absence and then the presence of a modern toilet in his ‘jungle village’, the artist lives out what decolonial and anticolonial philosopher Omar Rivera argues is “resistance … lived out in tension with the modern/colonial project”, as recalled by Deere. And this holds true for all the artwork that ‘Alienation’ as an exhibition displays.

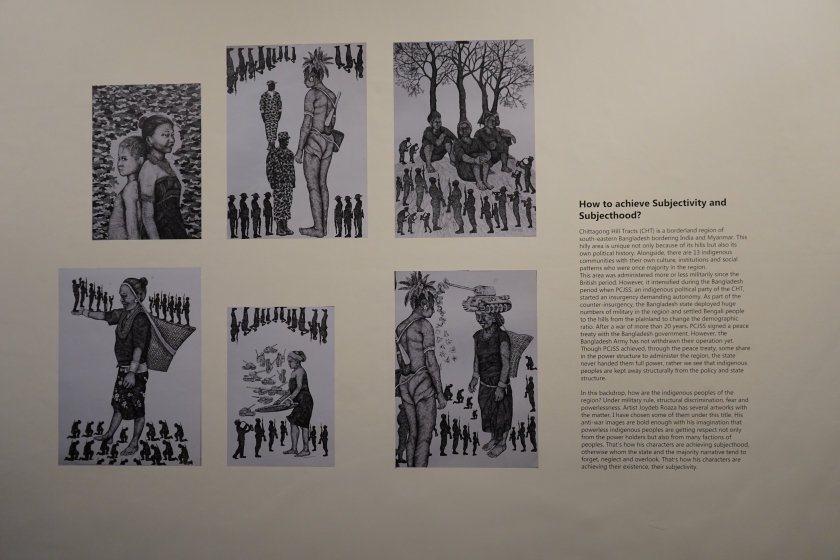

On the wall opposite Jayatu Chakma’s artwork ‘Extinguished Entity’, six monochrome ink-on-paper sketches were affixed without any frames. Arranged under the curatorial sub-heading ‘How to achieve Subjectivity and Subjecthood?’, these are the works of noted Indigenous artist Joydeb Roaja from the CHT. These untitled and rather small sketches, measuring 56×76 centimetres, draw the viewer to observe minutely what Roaja’s figures depict.

The allusion to the contemporary state of the Indigenous communities in the CHT is not lost on the viewer. From ‘Alienation’ by Adit Dewan, presented as part of ‘No Steady State,’ a group exhibition under Khoj and Goethe CISA 2024, held at Khoj Studios in March 2025. Photo: Shaheen Ahmed.

The sketches foreground Indigenous female and male figures in their traditional attire and paraphernalia, surrounded by multiple smaller figures of men in army fatigues carrying bayonets and guns.

Almost Kafaesque in tenor, the Indigenous figures, though larger than life in these sketches, appear to be surrounded by little men from the army with no room to escape them.

One such sketch shows three Indigenous figures sitting firmly on the ground as trees emerge from the top of their heads. The allusion to the contemporary state of the Indigenous communities in the CHT is not lost on the viewer.

Roaja, a member of the Tripura Indigenous community in the CHT, has closely witnessed the militarisation of the region. In a recent article on the current state of the CHT by Bangladeshi journalist Sanjoy Kumar Barua, he unambiguously writes that “Bangladesh’s security forces, long a dominant force in national politics, have now become de facto rulers in the CHT”, which has led to the Indigenous people living “… under constant surveillance, with their rights suspended in the name of national security. The consequences of this militarised rule are devastating. Indigenous communities are being pushed to the margins – culturally, economically and physically”.

Dewan, in his curatorial note for Roaja’s art, posits a seemingly innocuous but powerful question on the status of the Indigenous people of the CHT against the backdrop of their being kept away structurally from policy and the state. He answers it himself – they live under military rule, structural discrimination, fear and powerlessness.

Dewan frames these artworks as “anti-war images” in which Roaja shows how the “powerless Indigenous peoples of the CHT” have achieved respect from the state as well as mainstream society.

“That’s how his characters are achieving subjecthood, …[characters] whom the state and the majority narrative [otherwise] tend to forget, neglect and overlook,” Dewan adds.

One of most venerated voices in settler-colonial studies, the Australian anthropologist and ethnographer Patrick Wolfe, puts forth a poignant argument on the nature of settler colonialism. He argues that “settler colonisers come to stay; invasion is a structure not an event”. In simple words, settler colonialism by nature is not a momentary development; the process is undertaken through time and space.

In another argument, Wolfe writes that settler colonialism in most cases works through the logic of ‘elimination’. As he says, “Whatever settler colonialists may say … the primary motive for elimination is not race (or religion, ethnicity, grade of civilisation etc) but access to territory. Territoriality is settler colonialism’s specific, irreducible element.”

When viewing Roaja’s powerful art through these lens of settler-colonial discourse, the art simply does not remain as anti-war images, but transforms into powerful representations of the resistance by the Indigenous communities against an increasingly militarised state intent on occupying land.

This situation is a lived reality for the Indigenous peoples in the CHT. In a recent article on press freedom in Bangladesh after the Monsoon Revolution, writer Cyrus Naji briefly touches upon the prevailing censorship and media in the CHT.

Naji writes,

“Bangladeshi news outlets generally do not platform indigenous voices or provide in-depth coverage of the CHT for a number of reasons. Adivasis are ill-represented in the mainstream media and the country’s Bengali-dominated media outlets are unwilling to incur the wrath of military authorities. Any news must necessarily be gathered by local Adivasi reporters, who are especially vulnerable to intimidation by security forces and settler groups since they and their families must carry on living in the area”.

He further goes on to say that “media freedom is more or less meaningless in the CHT, which is still dominated by the military”. What is also interesting to note is that even in pieces critical of the Bangladeshi state, mainstream journalists from the country still carefully avoid using the term Indigenous for the communities of the CHT, rather employing state-approved terminologies like ‘Adivasi’, a fact that Dewan in his video artwork succinctly points out.

Roaja’s powerful sketches remind us once more of Kalpana Chakma, the Indigenous activist mentioned earlier. Jess Worth, while writing about Shahidul Alam’s exhibition, remarks that Chakma “dared to demand her rights … [and] had the audacity to speak out against military occupation and harassment by her own country’s army. She had the temerity to insist that, as a citizen of a free nation, she too needed to be treated as an equal.”

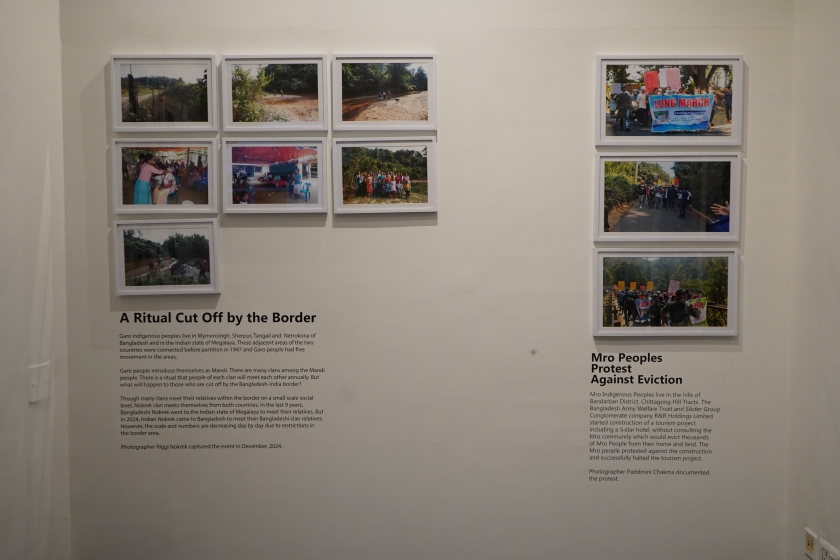

On the wall opposite the entrance to the studio were a set of seven framed photographs by Riggi Nokrek, arranged under the title ‘A Ritual Cut Off by the Border’. The photo story was a fascinating insight into the rituals of an Indigenous community cut off from historical and geographical bonds due to the colonial and post-colonial frontierisation policies.

Such documentation of the Indigenous peoples of the CHT being impacted by borders and frontiers is crucial. From ‘Alienation’ by Adit Dewan, presented as part of ‘No Steady State,’ a group exhibition under Khoj and Goethe CISA 2024, held at Khoj Studios in March 2025. Photo: Shaheen Ahmed.

Nokrek’s photos are a documentation of an annual ritual of the Nokrek clan of the Garo peoples in both the CHT and in Meghalaya. In this annual ritual, members of the clan cross over the international border to meet each other. From 2016 to 2023, members of the Nokrek clan from the CHT went to meet their ethnic kin in Meghalaya. In December 2024, clan members from Meghalaya crossed over to Bangladesh for this ritual meet, which Nokrek documented.

To understand this ritual is to understand the colonial project of frontierisation. Bal, the anthropologist, argues that “most non-Bengali minorities live in the border areas of the country … They live in the margins of the country …This does not mean that they have lived there forever.”

She goes on to argue that until the partition of the subcontinent in 1947, the Bangladeshi Garos did not live in an international borderland and the notion of a “… peripheral habitat becomes really tribalist when it is directly linked with ideas of civilisation”.

Such documentation of the Indigenous peoples of the CHT and their cultural, social and everyday life being impacted by borders and frontiers is crucial, as most narratives and communities get invisiblised due to the lack of official recognition or documentation.

There was also documentation by photographer Paddmini Chakma of a protest by the Mro peoples against eviction from their homes due to the construction of a tourism project in the Bandarban district in the CHT. This protest was successful, however, and their eviction was eventually stayed.

Next to Jayatu Chakma’s triptych ‘Extinguished Entity’ was ‘Furuncle of Development’ by Tufan Chakma. In this digital illustration, a Chakma woman is in the foreground in her traditional attire including jewelry, against the background of a destroyed and deforested valley with multiple earth excavators creeping on her body.

The ‘visibilisation’ of the CHT through this exhibition

As the opening event of the exhibition progressed, all the other curators who were part of CISA 2024 gave short speeches and introduced their curatorial ventures at Khoj.

Conspicuously, only Dewan was missing during the opening of the exhibition he curated. The irony is not lost when Dewan himself was unable to be at the opening of his own exhibition due to visa issues. The invisible was once again invisibilised.

Over an email interview with this writer, Dewan spoke about why he chose to curate such an exhibition in Delhi. “The particular reason for having curated an exhibition in Delhi is the CISA program which has that South Asian perspective,” Dewan said. “I wanted to show the issues [the] Indigenous peoples of Bangladesh are facing at a platform that has the South Asian perspective and it was great to do that through the CISA program,” he continued.

Since the Monsoon Revolution in Bangladesh in 2024, a renewed political focus has been thrust upon the country in the Indian subconscious. There have been discussions, television debates, op-eds, articles and more regarding the political developments in India’s neighbour.

However, one aspect in this whole political turmoil, if one may call it that, has been curiously invisible through most of the popular discourse. This invisibility or erasure – which as we have seen is not new but rather systemic – is of the discussion around the Indigenous peoples of the CHT.

The CHT, as discussed here, has seen systemic settler colonisation and the erasure of the body politic of the Indigenous body of the Chakma, the Mru, the Garo and other communities from this region.

These are the very reasons why Dewan’s ‘Alienation: The Case of the Indigeneity and the Indigenous Peoples of Bangladesh’ matters so much and why the artwork and the curatorial intervention needs more visibility and discussion.

Shaheen Ahmed is an academic and researcher. Her interests are in the visual arts, cinema, Indigenous studies and borderlands.

This article went live on June twenty-third, two thousand twenty five, at nine minutes past one in the afternoon.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.