Narrow Nationalism Has Won Over Cosmopolitanism Again, This Time in the Netherlands

Around the 1990s, Western political theorists began to build on the foundations of trade and financial liberalisation and globalisation, a structure of global political theory.

For long, political theory and international relations had little to do with each other. Political theorists tended to analyse and prescribe for nationally-bounded sovereign states. International relations theory was preoccupied with sovereign nation-states as the primary units of the international system.

In the aftermath of globalisation, Western political theorists went global. They realised that in an interconnected globalised world, both problems and the solutions to these problems have to be global. They also showed immense concern for poverty in countries of the global south, and inequalities between the global north and the global south. The influential theory that emerged from Western academia was that of global justice.

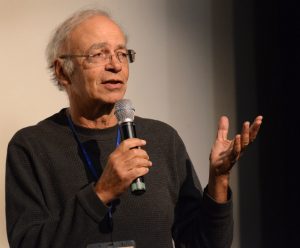

The ground for the global justice debate was inspired by a 1972 paper by the utilitarian philosopher Peter Singer on ‘Famine, Affluence and Morality’ in the reputed journal Philosophy and Public Affairs.

Photo: Mal Vickers/Wikimedia Commons. CC BY SA 4.0.

He argued that suffering and death from a lack of food, shelter and medical care are simply bad. If it is within the power of the citizens of the affluent West to prevent something bad from happening, without sacrificing anything of comparable moral importance, they are morally obliged to do so.

It does not matter that people who suffer for avoidable reasons are distant or proximate, or whether they are fellow nationals or needy foreigners. The need of strangers is as morally compelling as the need of neighbours or fellow citizens. It also does not matter that other people do or do not contribute their mite to the alleviation of poverty and misery; individuals should take on this moral responsibility.

And finally, he wrote, donating to famine relief is not a matter of charity but that of duty.

In a later work titled One World, Singer argued that since the world is interlinked, we need a transborder global ethics.

Imagine, he suggested, that you walk along a pond and see a small child in danger of drowning. It would be morally wrong not to try to save the child even if the suit we wear gets wet and is ruined. The cost is small compared to the good of saving the child.

We can have special feelings for those we love or those who are close to us, but this need not prevent us from helping others. There is no great difference between compatriots and the distant needy. Therefore, the middle-class American should give to the global poor something like one percent of his or her annual income. Basically, Singer focused on moral choices between spending on personal desires and helping the needy.

A number of political theorists living and working in what was once called the third world, were considerably sceptical, even outraged at this newest version of the ‘white man’s’ burden.

Could we in the global south afford to wait for citizens of the West to recognise their obligations to the distant needy? Should we be doing so?

Also Read: Palestine, Palestinians and the Western Liberal’s Burden

Justice it not dependent on charity. It has to be wrenched from the recalcitrant fists of elites through mass struggles and agitation. Despite some acrimonious challenges to the universality of global justice (for we who inhabit the world of the distant needy had no role to play in these theories except as a recipient) the debate taught us a valuable lesson.

There is need to expand the notion of duties and concern to people who live outside our borders. We should adopt a cosmopolitan approach towards human well-being. Cosmopolitanism moderates nationalist ambitions and opens many doors to solidarity across national borders. This is its virtue.

By the second decade of the 21st century, the context of political theory had dramatically changed. Across the world, the extreme right-wing came to command power. Under the impact of right-wing extremism, cosmopolitanism was thrown out of the window, and societies closed their doors and windows. They were now preoccupied with hostility against minorities, immigrants, ‘outsiders’ and neighbouring countries.

The imaginary enemy, right-wing populists told us, does not lurk on our border alone, it is within our own borders. Our fellow-citizens and those who sought citizenship became our enemies.

Never has the shift from cosmopolitanism to a narrow and ugly nationalism taken place so rapidly, except in the period leading up to the consolidation of German Nazism, which was openly hostile to the internationalism of the Left.

The notion of obligation towards the ‘distant needy’ or even the ‘proximate needy’ who did not belong to our religious community, were replaced by duty towards our own people with whom we were bound by ties of religion or race.

The distinction between cosmopolitanism and a nationalism that urges us to confine our loyalties to our own, came to mind as we read of another victory of the extreme right in Europe – the success of Geert Wilder’s Party for Freedom (PVV) in the Netherlands.

Geert Wilders. Photo: Wouter Engler/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0

The PVV, winning 37 of the 50 seats in parliament, is now a majority party. The Netherlands, for long identified with centrist politics, has now turned to the right. The implications are grim because Wilder is a polarising figure. He is against immigration, Islam and the European Union. He has opposed the construction of mosques, advocates strict control on drugs and urges a reduction in taxes.

In recent decades, most of Europe has been taken over by right-wing populists. Viktor Orban, the Prime Minister of Hungary, has directed the erection of fences to keep out refugees from war-torn Syria, captured the judiciary and other institutions, has openly encouraged crony capitalism, incorporated Christian values into the Constitution and is reportedly against gender studies in university curricula.

He has written the standard text of right-wing authoritarianism/populism: institutional capture and democratic backsliding. Right-wing authoritarianism has transformed former liberal democracies into illiberal electoral democracies. All that remains on the political landscape is elections. The script is surely familiar to Indians.

There are other examples that come to us from Europe. One is the rise of Georgia Meloni’s Brothers of Italy in Italy: nationalistic to the core, anti-immigrant and obsessed with state sovereignty. The increasing prominence of Marine Le Penn’s National Rally in France promises that another right-wing populist will come to power at some point in a country that expanded and popularised democracy first conceived of and implemented in Greece.

There are countless other examples of right-wing populists: Netanyahu in Israel and Putin in Russia, Donald Trump, the former President of the United States, and of course, the current leaders of India. They insistently subvert democracy, erode liberal ideas of obligation to others simply because they are human beings, dismiss inclusiveness and pluralism, mock equality and dignity, tolerance and secularism, corrode institutions, curtail civil liberties and openly head-hunt minorities.

In Europe and the US, the right head-hunts refugees who have been driven from their homes by wars not of their own making. Europe, once the site of the Renaissance and the rise of humanism and modern political values such as liberty, equality and fraternity, has become a graveyard of all these values.

Also Read: The Right Wing Is on the Rise Globally

This is not to misrecognise the fact that European countries violated their own values while colonising our world. But this is not the issue at hand, it requires a different story. The issue is as follows.

‘Why does Globalisation Fuel Populism?’ This is the title of the well-known essay authored by the economist Dani Rodrik of Harvard University in the 2021 Annual Review of Economics. There is, he suggests, compelling evidence that globalisation shocks, often working through culture and identity, have played an important role in driving up support for populist movements of the right-wing kind.

International integration has produced domestic disintegration in many countries. The populist response seems to have taken a mostly right-wing form.

There are other factors that intensify uncertainty amidst globalisation. Across the globe, one of the main consequences of globalisation is the dismantling of the welfare state.

In India, whatever social legislation was passed in the 2004-2014 period of UPA rule has been pulled to pieces by the NDA regime. The religious right-wing in the country has put into place a highly personalised system of the grant of benefits.

Social welfare is no longer an aspect of an appropriative state; it amounts to little more than the gift giving of a handful of grain and a little money. The grateful consumer is expected to show her, well gratitude, by casting a vote for the gift-giver. The citizen, as Yamini Aiyar puts it, has been reduced to a labharthi.

The dismantling of the welfare state that had been built brick-by-brick by social struggles, and in some cases a sympathetic judiciary, has led to tremendous insecurity. Privatisation of assets to industrial houses openly aligned to the ruling party has gravely reduced government jobs. Whatever jobs are left in the government sector have become the object of fervent desire, simply because they promise security.

And above all, globalisation brings a sense of homelessness because we no longer have a definite identity in an interconnected world. This was an identity that was carefully fashioned by the leaders of our freedom struggle.

Into this vacuum stepped in the religious right, flourishing the pennant of ‘we versus them’, advocating a strong state and an even stronger leader, and urging us to believe that the main issue is cultural homogeneity and the marginalisation of people who do not fit in.

Right-wing populists are dangerous because their politics is extremist, their ideology exclusionary, their enmity to those who do not belong palpable, their religious rhetoric cynical and opportunistic, and their chief desire to divide people so that they can rule.

It has been only a little over three decades that political theorists were speaking of a cosmopolitanism, a concept that Indians were already familiar with through the creative writings of Rabindranath Tagore.

Today we speak the language of provocation, taboos, censorship, coercion and bullying. Globalisation has battered the notion of obligation to each other simply because as human beings we owe each other. We now live in a Hobbesian state of nature, which is a state of war of all against all. We wait for a Leviathan to restore and reinforce our social contract – our Constitution that promises fraternity.

Neera Chandhoke was a professor of political science at Delhi University.

This article went live on November thirtieth, two thousand twenty three, at thirty minutes past three in the afternoon.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.