The Past, Present and Future of France’s Self-Inflicted Far-Right Surge

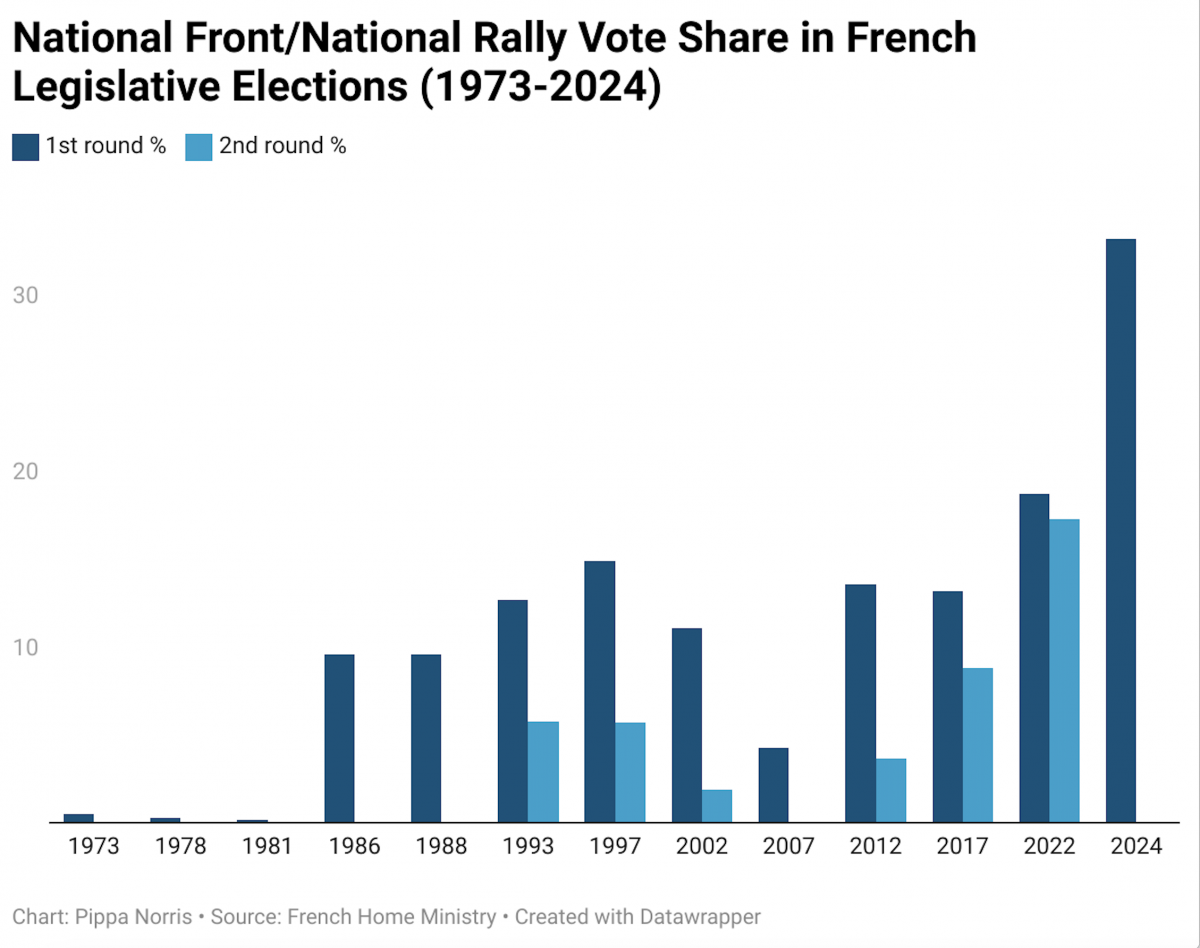

The first round of the French legislative elections has thrown the results that many had feared and predicted. The far-right party National Rally (formerly known as National Front) and its allies emerged first, bagging a third of the votes. The New Popular Front, an alliance of 25 left political formations, comes second with 28%. President Macron’s formation, Ensemble (‘Together’), is a distant third with 21% of the votes.

These results mark a substantive improvement for the National Rally (NR), which increased its vote share from 18.7% two years ago in the previous legislative election. It also improves on its recent performance in the European election of last May, where it scored 31%.

These results mark a historic shift in the French far-right’s performance for three reasons: First, the National Rally’s performance is compounded by a much higher participation: 68% against 47% in the first round of the 2022 legislative election and 51.5% in the European election. This means that the participation surge was driven as much by the increase in the popularity of the RN than by the democratic will to resist its rise.

Second, RN candidates came first in 297 of the 577 seats of the National Assembly across the territory. The NR, historically more confined to France's North-East and South-East regions, is now a truly national political force.

Third, this result pushes the far-right to the gates of power for the first time since World War 2 and their participation in the Vichy collaboration regime. While the peculiarities of the French electoral system do not guarantee a majority to the NR next week, there is a distinct possibility that the French far-right may form France’s next government.

The NR’s performance in the recent European election prompted President Emmanuel Macron to announce a snap election three weeks ago. This constitutionally un-required decision shocked many, including his prime minister and cabinet, who had not been consulted. Speculation abounds on the reasons that prompted Macron’s unilateral decision. Whatever these may have been, the plan backfired.

Emmanuel Macron. Photo: Instagram/elysee

The second round of the election will occur next Sunday, July 7. In the French system, candidates who secure 12.5% of the registered voters in their constituency qualify for the second round. When participation is low, two candidates usually qualify, ensuring the winner gets at least 50% of the votes. When participation rises, however, it becomes more likely for a third candidate to qualify, leading to a triangular contest. In that case, the winner takes it all, even if they do not reach the majority threshold. In the present context, this latter configuration favours the NR, whose candidates engaged in a triangular context may need to be ahead of their competitors to win seats.

In 2022, there were only eight triangular contests in a low-turnout election. This year, there could be theoretically triangular contests in more than 300 seats, given the distribution of votes. This is a theoretical number because third-ranked candidates can leave the race and call their voters to support the candidate who is most likely to defeat the far-right candidate. This ‘Republican Front’ system has historically enabled French parties to keep the far-right at bay in parliamentary elections. The few seats the NR successfully won in the past were in triangular contests where non-far-right parties and candidates failed to organise vote transfers.

Unclear messaging

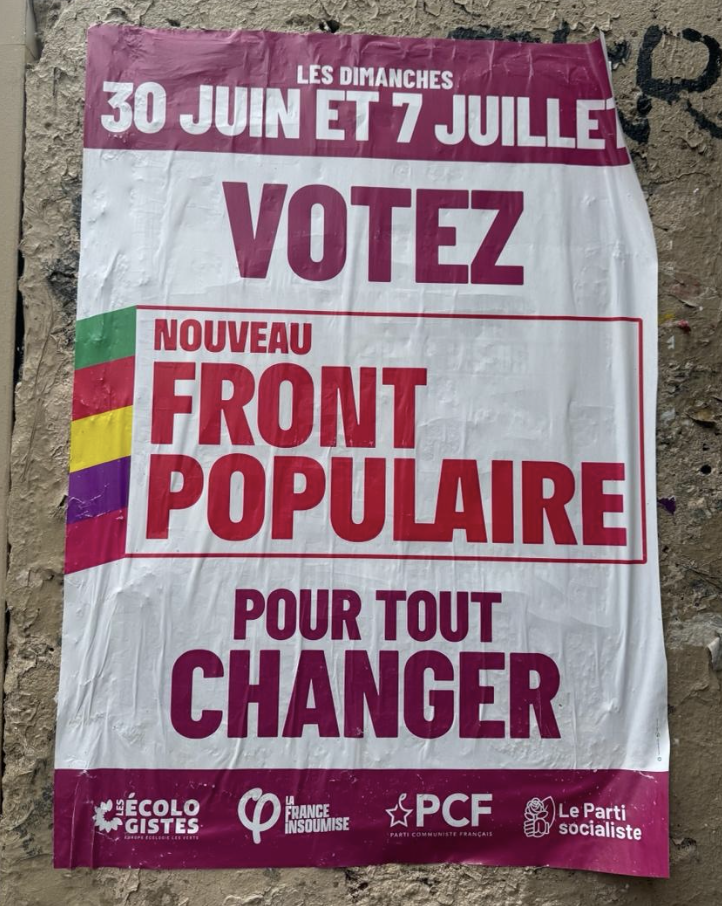

Political parties’ instructions are key to candidates’ decision to stay or leave the race. Upon the announcement of the results, the National Popular Front clearly declared that all its third-ranked candidates would desist from the second round and called their voters to support the non-far-right candidate in their respective constituencies.

On the other hand, President Macron and his prime minister chose a more ambiguous language to call voters to defeat the far-right. The prime minister spoke about the ‘moral duty’ to prevent the far-right from obtaining a majority but fell short of instructing all its third-rankers to desist from the second round. President Macron spoke about building a ‘broad and clearly democratic and republican union’ against the far-right in the second round. Still, it offered no detail on what this union could or should look like – neither clearly instructed their voters to transfer their votes to stronger far-right competitors to retain their pivot position.

'Vote New Popular Front to change everything.' Paris, May 2024. Photo: G. Verniers

Beyond an attempt to remain politically relevant, this hesitancy can be explained by Macron’s party’s detestation of one of the significant components of the New Popular Front, La France Insoumise (Unbowed France), led by Socialist Party dissident Jean-Luc Mélenchon. Unbowed France has emerged as France’s main opposition from the left over the past few years. They have been relentlessly criticising Macron’s policy and monarchic style of government. As a result, Macron’s party has been drawing a false equivalence between the left and the far right. This posture prevents many of its leaders today from calling for an effective democratic alliance against the far-right.

Ever since his election in 2017, President Macron has benefited from vote transfers in the second round of elections, notably from the left, to defeat the far-right. The decline of the traditional left (Socialist Party) and right parties (the Republicans) made him the most likely candidate to stand against the National Rally. However, these voters and the parties that represent them obtained very little in return regarding policy or power sharing. Macron has effectively governed as if his agenda had received majority support from voters, while many voted for him to obstruct the far-right. As a result, many voters are now tired of lending their vote to President Macron and calling on him to return the favour, which he and his party are not inclined to do.

These tensions explain why the mechanics of second-round elections and triangular contests have become somewhat gripped. In 2022, failure to establish ‘cordons sanitaires’ across all seats led to the far-right winning 89 seats in the National Assembly, a historical performance. As of this moment, there are still 165 triangular contests scheduled. Candidates have until Tuesday (July 2) to declare their intention to run or desist.

This is all to say that if institutional arrangements are still, in theory, favouring non-far-right parties, political tensions accumulated over the past seven years are likely to help the far-right to increase its presence in the National Assembly.

Why is this important?

First, these results matter for historical reasons. As mentioned earlier, this is the first time a far-right party is in a position to win a legislative election and come to power in France since the Vichy regime. The National Rally may deny today its filiation with the collaborationist regime, its pro-colonialism stance, and its ties with revisionist historians and known racists and antisemites. The reality is that it has never shed its adhesion to fundamental markers of the European far-right: defensive nationalism or the constant preoccupation with the defence of French national identity against its enemies, both interior and exterior; a biological conception of the nation (jus sanguinis versus jus soli) that would lead to transforming the rules of acquisition of French citizenship; an obsession for order and security over the protection of individual rights.

Voting during the snap elections in France. Photo: X/ @EmmanuelMacron

This leads them to hold a hard stance on immigration, to denounce the failure of immigrants – mainly Arabs and Muslims – to assimilate into French culture and values, to falsely pose immigration as a threat to France’s social security regime, to oppose the forces of cosmopolitanism and globalisation, to oppose European institutions and integration and to adopt a protectionist stance on economic matters.

Second, the arrival to power of the far-right in France would mark a shift in France’s stature in Europe that would have ripple effects well beyond its borders. Over the past few years, the far-right has progressed across Europe and the world, feeding on fears, crises, and uncertainties, pitting citizens against other designated categories of citizens and foreigners. A victory of the far-right in France would embolden the far-right across Europe. It would also consolidate its status of the National Rally as the leading far-right formation in Europe, a position it already assumes in the European Parliament alongside other parties.

And third, regarding French politics, it is safe to assume that Macron’s presidency is now effectively over, two years ahead of the next presidential election. Regardless of the configuration that will emerge from the second round, these elections have been the strongest signal of rejection he has faced since his rise in national politics ten years ago.

Theoretically, a coalition could be formed if no party obtains a majority of their own. However, this word does not (yet) fit into France’s political vocabulary. New political forms would have to be invented between deeply divided political actors. In all probability, his formation will lose control of the government, leading to some form of cohabitation (cohabitation regimes usually lead to a division of labor between the president and the government. The former tends to centre on foreign policy and engagements while losing grip on domestic matters).

Seven years ago, Macron attempted to create a new political form, a new centrist way, a synthesis of the centre-left (where he comes from originally) and the centre-right (where he effectively governs). In effect, his success was built on the ruin of traditional parties and the fear of the rise to power of the far-right. He failed to take advantage of France’s shifting political ground to create a new political party. Instead, he offered France a lonely exercise of power backed by a dwindling parliamentary majority. This failure to capitalise on the decline of mainstream parties and the adoption by his government of some of the far-right’s pet themes, starting with immigration and order – contributed to the normalisation of the far-right in France.

Gilles Verniers is Karl Loewenstein Fellow and Visiting Assistant Professor of Political Science at Amherst College. Views are personal.

This article went live on July first, two thousand twenty four, at thirteen minutes past two in the afternoon.The Wire is now on WhatsApp. Follow our channel for sharp analysis and opinions on the latest developments.